值与对象#

- 值是一个纯粹的数学抽象概念

- 对象是一个在内存中占据了一定空间的有类型的东西

- 区分对象和值的方法非常简单: 是否有标识

- 任何对象都必然可以被引用, 引用做为一个对象的别名, 当然也是对象的一种标识

引用#

- 引用在语义上是对象的别名

- 任何一个引用 (无论是左值引用还是右值引用) 类型的变量, 都必然是其所绑定对象的 别名, 因而都必然是左值.

缺失的拼图#

- C++11 之前, 表达式分类为左值表达式和右值表达式, 简称左值和右值

- 左值都对应着一个明确的对象, 从而也都必然可以通过

&进行取地址操作 - 而右值表达式虽然肯定都不能进行取地址操作, 但在有些场景下, 也会隐含着创建一个临时对象的语义

用引用去匹配赋值或函数参数等, 有如下场景:

- const lvalue reference ->

Foo& ref = foo; - non-const lvalue reference ->

const Foo& ref = foo - const rvalue reference ->

const Foo& ref = Foo(10) - non-const rvalue reference -\>

Foo& ref = Foo(10)

只有 non-const rvalue reference 无法表达, 因为一个右值不能被 T & 类型的参数匹配, 修改一个调用后即消失的临时对象上, 没有任何意义, 反而会导致程序员犯下潜在的错误, 因而还是禁止了最好.

虽然对临时对象的修改是无意义的, 但 non-const rvalue reference 在一些情况下可能是合理且非常有用的.

move 语义#

C++11 之前, 只有 copy 语义, 这对于极度关注性能的语言而言是一个重大的缺失. 比如:

std::string str = s1 + s2;这种直观的写法必须忍受一个 s1 + s2 所导致的中间临时对象到 str 的拷贝开销, 即便那个中间临时对象随着表达式的结束会被销毁 (更糟的是, 销毁所伴随的资源释放, 也是一种性能开销).

对于 move 语义的急迫需求, 到了 C++11 终于被引入. 其直接的驱动力很简单: 在构造或者赋值时, 如果等号右侧是一个中间临时对象, 应直接将其占用的资源直接 move 过来 (对方就没有了).

而能够被 move 走资源的临时对象, 恰恰是之前缺失的那种引用类型: non-const rvalue reference.

为了让一个构造函数或者赋值操作重载函数能够识别出来这是一个临时变量, 我们需要有一种新的表示法, 即右值引用 T&&. 比如:

struct Foo {

Foo(const Foo&); // copy ctor

Foo(Foo&&); // move ctor

Foo& operator=(const Foo&); // copy assignment

Foo& operator=(Foo&&); // move assignment

};通过这样的方式, 让 Foo foo = Foo(10) 或 foo = Foo(10) 这样的表达式, 都可以匹配到 move 语义的版本. 与此同时, 让 Foo foo = foo1 或 foo = foo1 这样的表达式, 依然使用 copy 语义的版本.

右值引用变量#

一个 non-const rvalue reference 类型的变量, 允许匹配 non-const lvalue reference 类型的参数, 但这会导致一个看起来很矛盾的现象, 比如:

void f(Foo& foo) { foo.a *= 10; }

Foo&& ref = Foo{10};

f(ref); // 允许

f(Foo{10}); // 不允许这背后的差异究竟意味这什么?

其实, 看似 ref 被定义的类型为右值引用, 但这, 仅仅约束它的初始化: 只能从一个右值进行初始化. 但一旦初始化完成, 临时对象的生命将被扩展, 会在其被创建的 scope 内始终有效, 它就和一个左值引用再也没有任何差别: 都是一个已存在对象的标识.

下面是几个例子:

Foo foo {10};

Foo&& ref = Foo{10};

// Foo&& ref = foo; // 不合法, 右值引用只能由右值初始化

Foo copy = ref; // copy, not move

Foo& rref = ref;

// Foo&& rref = ref; // 不合法, ref 是个左值注意 auto copy = ref 调用的是拷贝构造. C++ 规定产生临时变量的表达式是右值, 而任何变量都是一个对象的标识, 因而都是左值 , 哪怕变量类型是 右值引用. 因而, 右值匹配 move constructor, 左值匹配 copy constructor.

函数参数也没有任何特别之处, 无非是其可访问范围被限定在函数内部. 调用一个函数时, 传递实参的过程, 就是一个对参数 (变量)进行初始化的过程, 而初始化的细节与一个普通变量没有任何差别:

void stupid(Foo&& foo) {

foo.a += 10; // 在函数体内, foo 的性质与一个左值引用毫无差别

// blah ...

}

stupid(Foo{10}); // 在执行函数体之前, 进行参数初始化: Foo&& foo = Foo{10}速亡值#

如果我就是想把一个左值 move 给另外一个对象, 该怎么办? 最简单的选择是通过 static_cast 进行类型转换:

Foo foo{10};

Foo&& ref = Foo{10};

Foo obj1 = static_cast<Foo&&>(foo); // move

Foo obj2 = static_cast<Foo&&>(ref); // move这里矛盾就来了:

- 只有右值才能匹配

move构造, 所以static_cast<Foo&&>(foo)表达式是一个右值 static_cast<Foo&&>(foo)表达式返回的类型是一个引用, 这不符合右值的定义

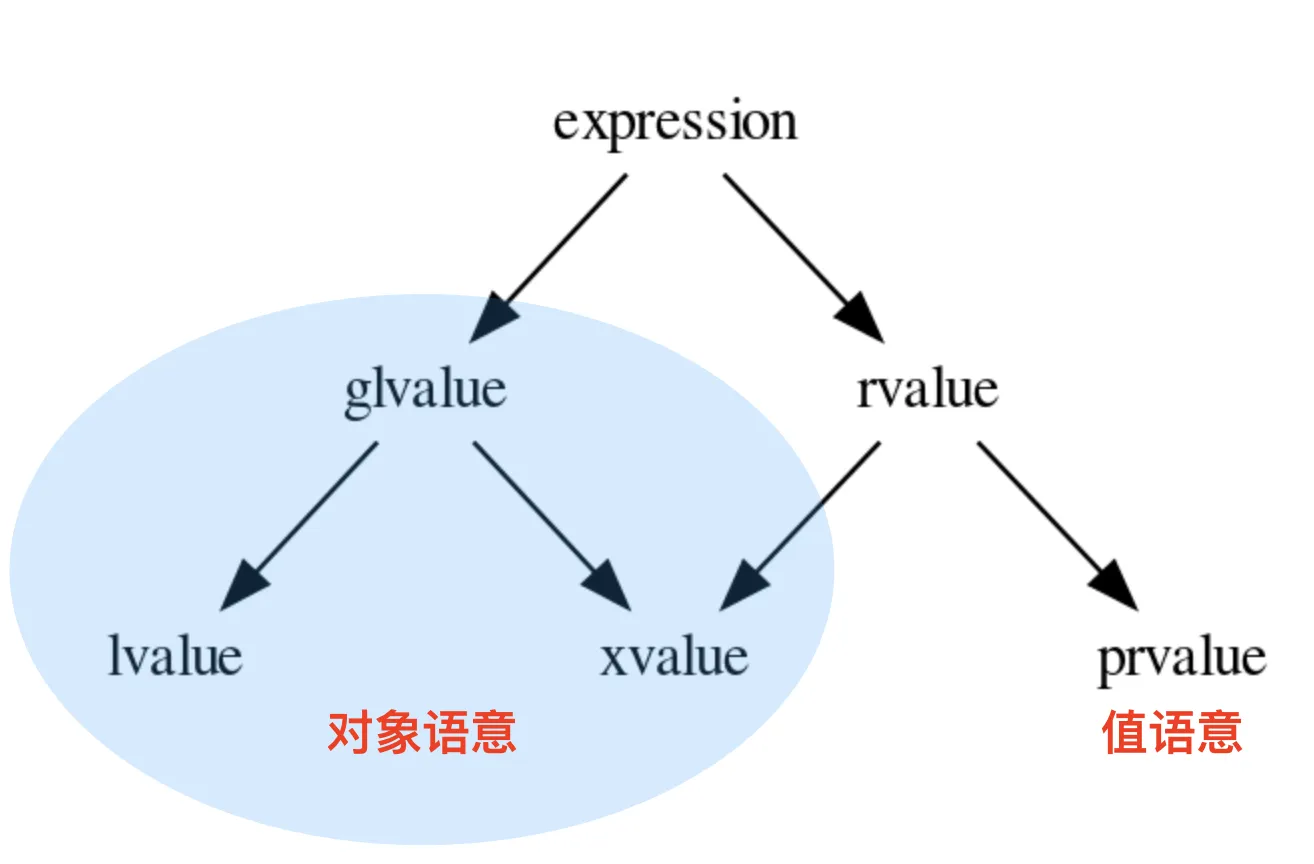

对于这种既有左值特征, 又和右值临时对象一样, 可以用来初始化右值引用类型的变量的表达式, 只能将其归为新的类别:

- C++11 给这个新类别命名为速亡值 (eXpiring value, 简称 xvalue)

- 原来的右值重新命名为纯右值

- 而速亡值和纯右值合在一起称为右值, 其代表的含义是所有可以直接用来初始化右值引用类型变量的表达式

- 速亡值又和左值一起被归类为泛左值 (generalized lvalue, 简称 glvalue)

关于速亡值:

- 速亡值是对象语义

- 除了

static_cast<T&&>(expr)这样的表达式之外, 任何返回值为右值引用类型的函数调用表达式也属于速亡值 - 速亡值可以匹配

move构造,move赋值函数, 以及任何其它参数类型为右值引用的函数 - 速亡值未必真的会速亡 (expiring), 它只是能用来初始化右值引用类型的变量而已, 只有用到

move场景下, 它才会真的导致所引用对象的失效 - 对速亡值取地址没有意义, 因此对其取地址操作被强行禁止

- 函数地址被

move毫无意义, 因此FunctionType&&的类别为左值

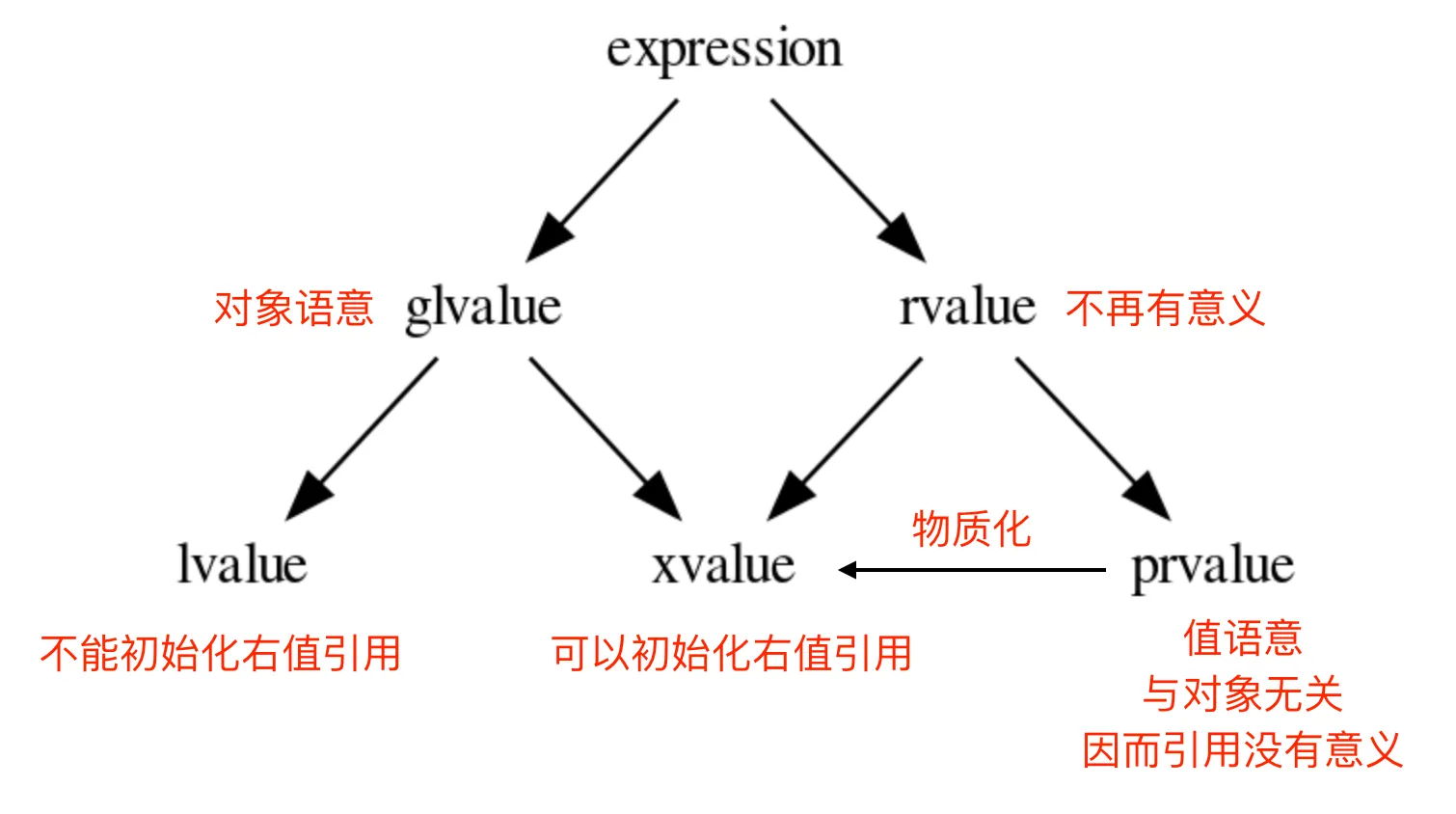

对象 or 值? C++17 的语义改进#

在 Foo 是一个 class 的情况下, Foo(10) 是一个对象还是一个值?

在 C++17 之前, 这个表达式的语义是一个临时对象, 因为它可以被右值引用, 能被引用的必然是对象. 但后来人们发现, 将其定义为对象语义, 在一些场景下会带来不必要的麻烦:

Foo foo = Foo(10);它的语义是: 构造一个临时对象, 然后 copy/move 给左边的对象 foo.

注意, 只要 Foo(10) 被定义为 对象, 那么 copy/move 语义也就变得不可避免, 这就要求 class Foo 必须要隐式或显式的提供 public copy/move constructor, 即便编译器肯定会将对 copy/move constructor 的调用给优化掉, 但这是到优化阶段的事, 而语义检查发生在优化之前. 如果 class Foo 没有 public copy/move constructor, 语义检查阶段就会失败. 如果程序员不希望 class Foo 可以被 copy/move, 这就带来了麻烦.

于是到了 C++17, 对于类似于 Foo(10) 表达式的语义进行了重新定义, 它们不再是一个对象语义, 而只是一个值. 而这个值, 通过等号表达式, 赋值给左边的对象, 正如 int i = 10 所做的那样. 从语义上, 不再有对象间的 copy/move. 因而在 C++17 之后, 下面的语句在语义上 (而不是编译器优化上) 完全等价:

Foo foo = Foo{Foo{Foo{10}}}

<=> Foo foo{Foo{Foo{10}}

<=> Foo foo = Foo{Foo{10}}

<=> Foo Foo{Foo{10}}

<=> Foo foo = Foo{10}

<=> Foo foo{10}纯右值物质化#

现在再来看这个语句:

Foo&& foo = Foo(10);将 Foo(10) 表达式的语义重新定义为值后, 类似上面的语句就显得有些问题, 因为引用一个值是逻辑上是讲不通的. 所以这中间隐含着一个过程: 纯右值物质化, 即将一个 纯右值, 赋值给一个 临时对象, 其标识是一个无名字的右值引用, 即速亡值. 然后再将等号左边的引用绑定到这个速亡值对象上.

纯右值物质化的过程还发生在其它场景. 比如:

Foo(10); // 纯右值

Foo(10).m; // 速亡值

using Array = char [10];

Array{}; // 纯右值

Array{}[0]; // 速亡值

static_cast<T>(expr); // expr 是一个纯右值, T 是一个右值引用类型C++17 之后的参数匹配从匹配行为上没有变化, 但语意上却有了变化. 最终导致匹配右值引用版本的不是纯右值类别, 而是纯右值进行物质化后得到的速亡值, 是用速亡值初始化了函数的对应参数. 比如下面的参数匹配:

void func(Foo&&); // #1

void func(const Foo&); // #2

Foo&& f();

func(Foo{10}); // #1

func(f()); // #1

Foo foo{10};

func(foo); // #2

Foo&& foo1 = Foo{10};

func(foo1); // #2

Value Category#

-

prvalue is exactly temporaries:

- Literals, including enumerators;

- Result of function call that returns value type;

- Operators & conversions that create temporaries;

-

xvalue (eXpiring value):

- Data members of rvalue;

- Expressions that creates rvalue reference;

- And some special cases including

?:,[]and,;

-

lvalue is basically “long-living” data:

- Named variables, Data members of lvalue, static data;

- string literals;

- Result of function call that returns lvalue reference type;

- Operators & conversions that are equivalent to creating the lvalue reference to the original;

-

For

struct A { string& b; },c = std::move(a.b)<=/=>c = std::move(a).b. -

const lvalue reference (

const Type&): to be consistent with C++98, it can refer to any value category but it’s read-only. -

As parameters, the overload resolution rule is:

- non-const lvalue ->

&, otherwiseconst&; - const lvalue ->

const&; - rvalue ->

&&, (and thenconst&&, ) otherwiseconst&.

- non-const lvalue ->

-

Return value of const value type is almost always useless.

decltype#

- For deducing the type of variable name & member access, just same as the declared type.

- For deducing the type of expression:

decltype(prvalue)→ value type.decltype(lvalue)→ lvalue reference.decltype(xvalue)→ rvalue reference.

decltype(auto): same asdecltype(foo) var = foo;

int foo { 1 };

decltype(auto) var { foo }; // -> int

decltype(auto) ref { (foo) }; // -> int&Reference Qualifier#

&will bind lvalue only and&&will bind rvalue.- Case:

std::optional/std::expectedoptimization. - Can be used to avoid lifetime problems.

class Person {

std::string name_ = "test";

public:

const std::string& getName() const& {

return name_;

}

std::string getName() && {

return std::move(name_);

}

};

Person recruitNewPerson() {

return Person{};

}

int main() {

// for (char ch : recruitNewPerson().getName()) {

// same as

auto&& range = recruitNewPerson().getName();

for (auto pos = range.begin(); pos != range.end(); pos++) {

// ...

}

}Persontemporary itself won’t extend its lifetime.- Solution: use reference qualifier!

- For lvalue return reference;

- For rvalue return value type!

std::moveis because rvalue basically means the value can be stolen, so moving away the member is reasonable and efficient.

- Since C++23, lifetime of most temporaries generated by expressions in range-initializer will be extended automatically.

- Besides preventing bug, it could be utilized to boost performance.

std::vector<std::string> names;

names.push_back(std::move(person).getName());Deducing this#

class Person {

std::string name_ = "test";

public:

const std::string& getName(this const Person& self) {

return self.name_;

}

std::string getName(this Person&& self) {

return std::move(self.name_);

}

};- Similar to reference qualifier.

- It can make the explicit object be of value type!

- You can define recursive lambda in this way.

auto fib = [](this auto self, int n) {

if (n < 2) return n;

return self(n - 1) + self(n - 2);

};Copy Elision#

prvalue copy elision#

- The time when prvalue is used to construct a real object is delayed as much as it can.

- When the object is finally constructed, it’s said the prvalue is materialized.

- If the result object is not lvalue, then it’s materialized as xvalue

Return value optimization (RVO)#

- RVO: not create a temporary (and destrcut the original one).

- NRVO (Named RVO) has many restrictions to apply:

- Must be a name;

- Must be local variable, with the type same as function return type;

- Must NOT be the parameter;

- Must be the only returned variable in all return statements.

- That’s why we say return

std::move(x)may decrease performance.

Implicit Move#

- All non-volatile variables with automatic storage duration (including parameters) or their rvalue references will be seen as xvalues in return.

// Since C++ 23

decltype(auto) stupid() { // -> Foo

Foo foo;

return foo; // NOOOOO!

}

decltype(auto) stupid() { // -> Foo&&

Foo foo;

return (foo); // NOOOOO!

}Conclusion#

- if prvalue -> RVO

- elif local variable & satisfies restrictions -> NRVO

- elif local variable -> implicit move

- elif -> could use

std::move

Analyzing Performance of Move Semantics#

- Parameter choice for normal ctors

- Two choices:

- Value type;

- Overloading by

const&and&&.

- The performance gap between these two choices are just 1 move ctor and 1 empty-state dtor.

- If the move ctor and empty-state dtor for the parameter is cheap enough, using value type is totally acceptable.

- e.g.

std::vector<std::string>matches the former, andstd::array<std::string, 1000>

- Two choices:

- For assigning to an object, like in setter, then it’s your duty to think about the efficiency of future operations.