Types related to sizeof#

- Two special integral type aliases defined in

<cstddef>:std::size_t- It’s unsigned, and the signed version

ssize_tis not standard. - Use

zas literal suffix for signedstd::size_t, andzuas literal suffix forstd::size_t.

- It’s unsigned, and the signed version

std::ptrdiff_t- The return type of subtracting two pointers.

- It’s signed.

- It is needed because on some old platforms, you need segments to represent the array, and pointer can only operate address in a segment.

Iterators#

Introduction#

-

There are 6 kinds of iterators:

- Output iterator: write-only access,

*it = val,it++,it1 = it2 - Input iterator: read-only access,

*it,it++,it1 = it2 - Forward iterator: same as input iterator,

==,!=, default construct- e.g. single linked list

- Bidirectional iterator: same as forward iterator,

it--- e.g. double linked list, map

- Random access iterator: same as bidirectional iterator,

+,-,+=,-=,[]- e.g. deque

- Contiguous iterator: same as random access iterator, memory occupied by iterators is contiguous

- e.g. vector, string

- Output iterator: write-only access,

-

Iterators are as unsafe as pointers!

- They can be invalid, e.g. exceed bound.

- Even if they’re from different containers, they may be mixed up!

- Some may be checked by high iterator debug level.

Usage#

-

All containers can get their iterators by:

.begin(),.end().cbegin(),.cend(): read-only access.- Except for forward-iterator containers (e.g. single linked list):

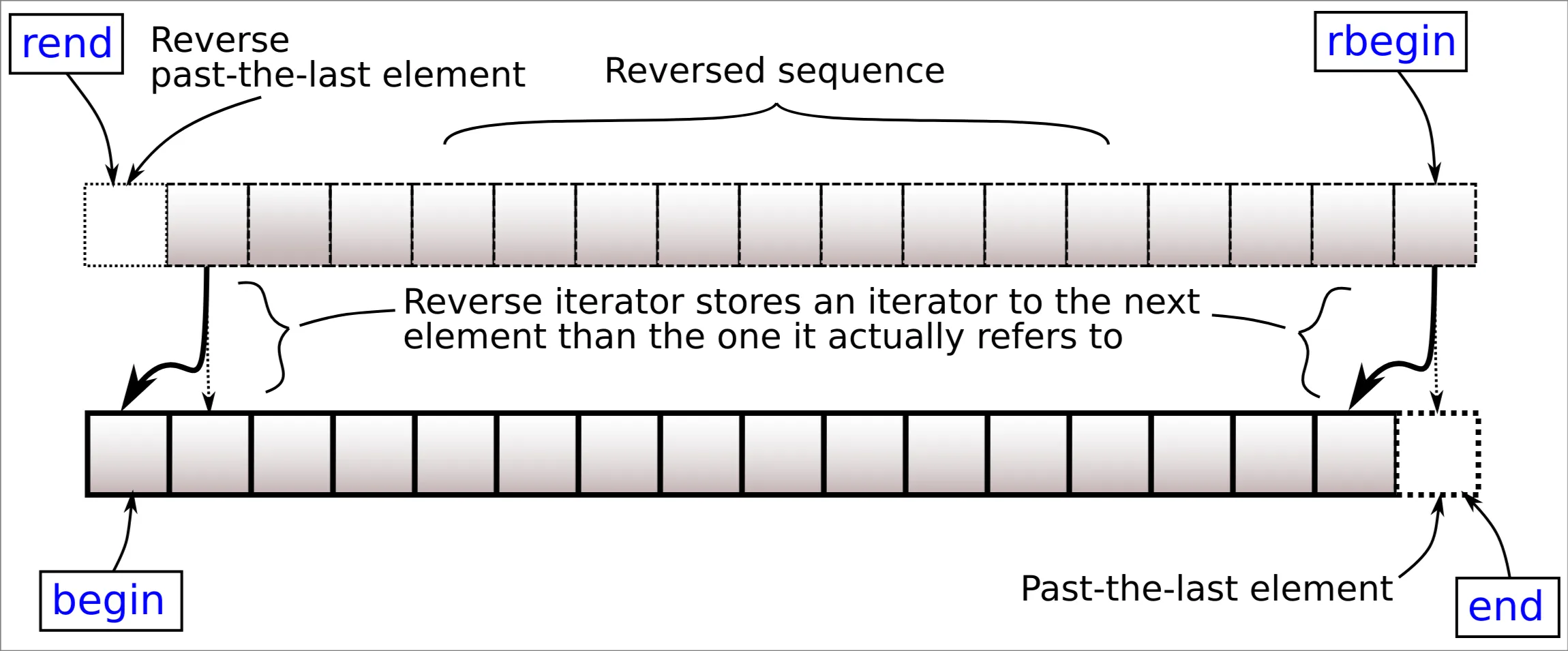

.rbegin(),.rend(),.crbegin(),.crend(): reversed iterator, i.e. iterate backwards.

-

You can also use global functions to get iterators.

- e.g.

std::begin(vec),std::end(vec). - You can also apply them to arrays (not pointer type) since pointers inherently act as iterators.

- e.g.

-

The

<iterator>header provides generic functions for iterator manipulation:std::advance(it, n): Implementsit += nfor non-random-access iterators (accepts negativen)std::next(it, n = 1): Returns copy ofitadvanced bynpositionsstd::prev(it, n = 1): Returns copy ofitreversed bynpositionsstd::distance(it1, it2): Returns count between iterators ( for random-access, otherwise)

-

They have ranges-version, e.g.

std::ranges::begin -

Iterators provide some types to show their information.

std::iter_value_t<IteratorType>std::iter_reference_t<IteratorType>std::iter_const_reference_t<IteratorType>std::iter_difference_t<IteratorType>std::iterator_traits<IteratorType>::pointer

Iterator adaptor#

- One category of iterator adaptors wraps existing iterators to provide specialized functionality.

- e.g.

std::reverse_iterator r { p.begin() } - You can get the underlying iterator by

.base(). - You can also use functions like

std::make_reverse_iterator()to create it.

- e.g.

template <typename T, std::size_t SIZE>

class Stack {

T arr[SIZE];

std::size_t pos = 0;

public:

T pop() {

return arr[--pos];

}

Stack& push(const T& t) {

arr[pos++] = t;

return *this;

}

auto begin() {

return std::reverse_iterator(arr + pos);

}

auto end() {

return std::reverse_iterator(arr);

}

};

int main() {

Stack<int, 8> s;

s.push(5).push(15).push(25).push(35);

for (int val: s)

std::print("{} ", val);

std::println("");

}int main()

{

std::vector<int> v { 0, 1, 2 };

auto vcrb1 { v.crbegin() };

std::reverse_iterator vcrb2 { v.cbegin() };

const auto b = std::is_same_v<decltype(vcrb1), decltype(vcrb2)>; // true

for (auto it = v.crbegin(); it != v.crend(); it++) {

auto itb = it.base(); // reverse_iterator

auto itbb = it.base().base(); // int*

std::println("*it: {}, *itb(): {}, *itbb: {}", *it, *itb, *itbb);

}

return 0;

}- Do not access

.end()with*, only use as position specifier.

using std::operator""s;

void print(auto const remark, auto const& v)

{

const auto size = std::ssize(v);

std::cout << remark << '[' << size << "] { ";

for (auto it = std::counted_iterator{std::cbegin(v), size};

it != std::default_sentinel; ++it)

std::cout << *it << (it.count() > 1 ? ", " : " ");

std::cout << "}\n";

}

int main()

{

const auto src = {"Arcturus"s, "Betelgeuse"s, "Canopus"s, "Deneb"s, "Elnath"s};

print("src", src);

std::vector<decltype(src)::value_type> dst;

std::ranges::copy(std::counted_iterator{src.begin(), 3},

std::default_sentinel,

std::back_inserter(dst));

print("dst", dst);

}- Another is created from containers to work more than “iterate”.

std::back_insert_iterator{container}:*it = valwill callpush_back(val)to insert.std::front_insert_iterator{container}: callpush_front(val)to insert.std::insert_iterator{container, pos}: callinsert(pos, val)to insert, where pos should be an iterator in the container.- You can also use functions like

std::back_insert()to create them.

Stream iterator#

int main()

{

std::istringstream str("0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4");

std::partial_sum(std::istream_iterator<double>(str),

std::istream_iterator<double>(),

std::ostream_iterator<double>(std::cout, " "));

std::istringstream str2("1 3 5 7 8 9 10");

auto it = std::find_if(std::istream_iterator<int>(str2),

std::istream_iterator<int>(),

[](int i){ return i % 2 == 0; });

if (it != std::istream_iterator<int>())

std::cout << "\nThe first even number is " << *it << ".\n";

//" 9 10" left in the stream

}std::vector<int> vec;

std::copy(

std::istream_iterator<int> { std::cin },

std::istream_iterator<int> {},

std::back_insert_iterator { vec }

);

std::copy(

vec.begin(),

vec.end(),

std::ostream_iterator<int> { std::cout, "\n" }

);Iterator invalidation#

- The iterator is designed as a wrapper of the pointer to the element.

- An iterator may be unsafe because it may not correctly represent the state of the object it is iterating.

- Reallocation, the original pointer is dangling;

- On insertion & removal, so the original pointer points to an element that it may not intend to refer.

- They are thread-unsafe.

Sequential containers#

array#

-

std::array<T, size>- Same as

T[size]. - Always preserves size (will not decay).

- Can copy from another array.

- Do more things like bound check.

- Allocated on stack.

- Same as

-

Ctor

- May need adding an additional pair of paratheses.

struct S {

int i;

int j;

};

std::array<S, 2> arr {{ { 1, 2 }, { 3, 4 } }};-

Element access

operator[]vs.at(): index-based element access..at()performs bounds checking (throwsstd::out_of_range).

.front()/.back(): access first/last element of array.- Contiguous iterators.

.data(): returns pointer to underlying array storage.- Zero-sized arrays:

std::array<T,0>is allowed but element access operations cause UB.

-

Some additional methods

.swap(): same asstd::swap(arr1, arr2)..fill(val): fill all elements asval.std::to_array(c_style_array): get a std::array from a C-style array..size(): get size (returnstd::size_t)..empty(): get a bool denoting whethersize == 0.

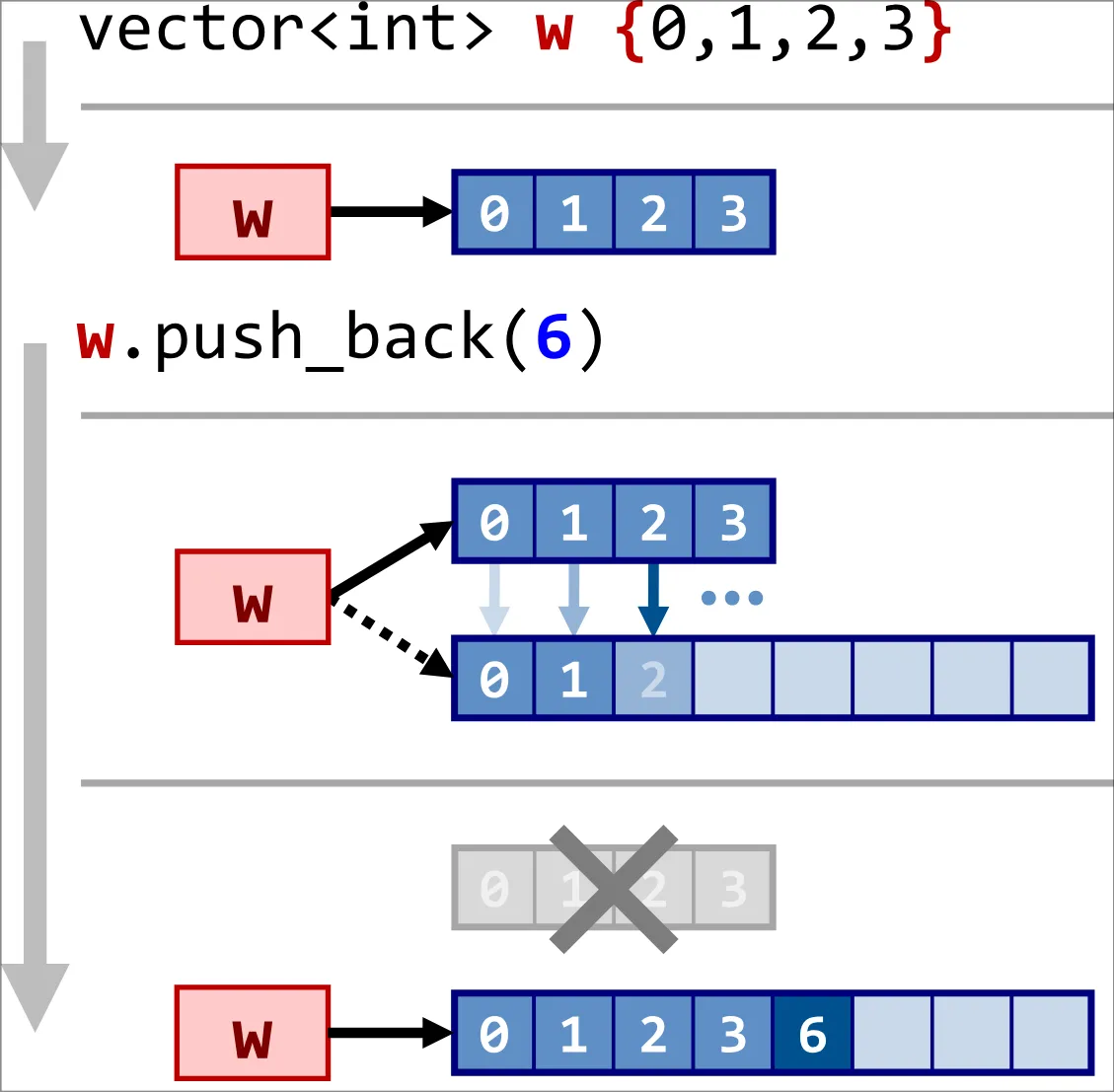

vector#

std::vector<T>is dynamic array which can be resized.- Supports random access

- Occupies contiguous space.

- It has members as: pointer to content, size and capacity (three pointers in implementation).

- When inserting and removing elements at the end the complexity is amortized ; If not at end, it’ll be .

Reallocation strategy#

- Despite other compilers reducing the growth factor to 1.5, gcc has staunchly maintained its factor of 2. This makes

std::vectorcache-unfriendly and memory manager unfriendly.

Usage#

Ctor#

- Default ctor.

- Copy ctor & Move Ctor.

(size_t count, const T& elem = T{})- e.g.

std::vector<int> vec(3, 2);

- e.g.

(InputIt first, InputIt last)- copy elements from

[first, last)into the vector.

- copy elements from

(std::initializer_list)- e.g.

std::vector<int> vec { 2, 2, 2 };

- e.g.

- All ctors have an optional allocator parameter.

Element access#

- Same as

std::array

Capacity operations#

.capacity().reserve(n): expand the memory to make thecapacity = nif it’s greater than the current capacity.- This is dramatically important in some parallel programs because of iterator invalidation.

.shrink_to_fit: request to shrink the capacity so that capacity == size.

Size operations#

.size().empty(): get a bool denoting whethersize == 0..resize(n, obj=Object{}): make thesize = n.- If the original size is

n, nothing happens. - If greater than

n, elements in[n, end)will be removed. - If less than

n, new elements will be inserted, and their values are allobj.

- If the original size is

.clear(): remove all things.- Size will be 0 after this., but the capacity is usually not changed!

Element operations#

-

.pop_back() -

.push_back(obj) -

.emplace_back(params): insert an element constructed byparamsat the end.- It returns reference of inserted element.

-

.emplace(const_iterator pos, params): insert an element constructed byparamsinto pos. -

.insert(const_iterator pos, xxx): insert element(s) into pos,xxxis similar to params of ctor:(pos, value)(pos, size_t count, value): insertcountcopies ofvalue.(pos, InputIt first, InputIt last): insert contents from[first, last).(pos, std::initializer_list)

-

.erase(const_iterator pos)/.erase(const_iterator first, const_iterator last)- insert/erase will return next valid iterator of inserted/erased elements, so you can continue to iterate by

it = vec.erase(...). - They make iterators after the insertion/removal point invalid.

- insert/erase will return next valid iterator of inserted/erased elements, so you can continue to iterate by

-

Interact with another vector

.assign(xxx): similar to ctor.swap(vec): same asstd::swap(vec1, vec2).

-

Ranges-related methods

.assign_range(Range): can copy any range to the vector..insert_range(const_iterator pos, Range).append_range(Range): insert range from the end.

-

If you just want to remove all elements that equals to XXX in a vector, it’s costly to use erase repeatedly ( obviously)

Specific: std::vector<bool>#

std::vector<bool>- It is regulated to be compacted as “dynamic array of bit”.

operator[]returns a proxy class of the bit. (For const method, it still returnsbool.)automay be proxy which holds the reference of the bit, so this will change the vector!- Range-based for may use

auto, so pay attention if you’re doing so!- Besides, since the returned proxy is a value type instead of reference, so the returned object is temporary!

- Then, you cannot use

auto&when iterating vector, though it’s right for other types. - To sum up, use

autorather thanauto&if you want to change elements of vector, use constauto&orbool(or usestd::as_count()) if you don’t want to change.

- It supports

operator~,filp()andstd::hash

Related: bitset#

std::bitsit<size>- Not a container and not provide iterators.

- It provides more methods, which makes it a more proper way to manipulate bits.

&,|,^,~,<<,>>set(),set(pos, val = true),reset(),reset(pos),flip(),flip(pos)all(),any(),none(),count()- It can also be input/output by

>>/<<.

- It can be converted to

std::string/unsigned long longby.to_string(zero = ‘0’, one = ‘1’)/.to_ullong(). - It can also be constructed by a

std::string/unsigned long long, i.e.(str, start_pos = 0, len = std::string::npos, zero = ‘0’, one = ‘1’). - Other similarities to

std::vector<bool>- You can access the bit by

operator[], which returns a proxy class too (for const methods,booltoo).- There is no

.at(pos)in bitset, but a bool.test(pos), which will do bound check.

- There is no

operator==,.size(),std::hash

- You can access the bit by

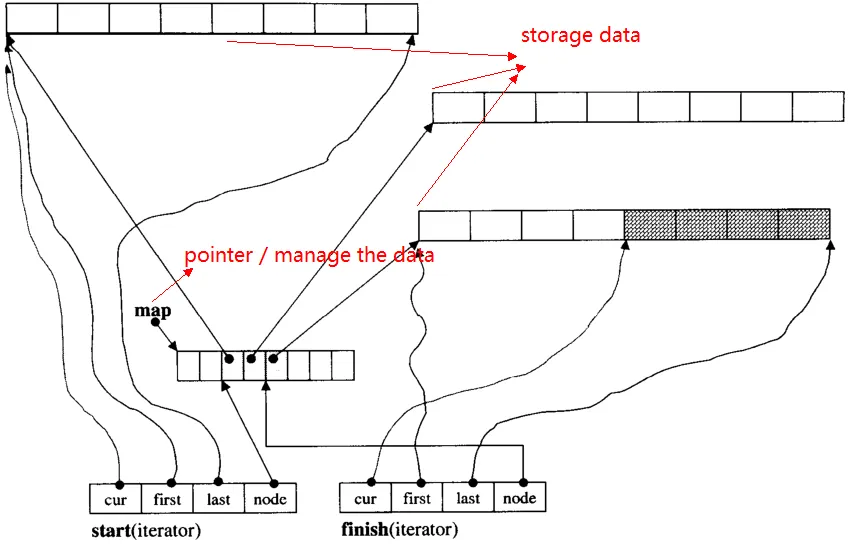

deque#

Introduction#

- Double-Ended Queue

- Allows fast () insertion and deletion at both its beginning and its end.

- Expansion is cheaper than

std::vector. - Insertion and deletion at either end of a deque never invalidates pointers or references to the rest of the elements.

- Elements of are not stored contiguously.

Usage#

- Same as

std::vector, but also provides the following methods..push_front().emplace_front().pop_front().prepend_range()

Implementation#

-

The typical implementation is using a dynamic circular queue (called map) whose elements are pointers.

- Each pointer points to a block, with many objects stored there.

- The block size is fixed, e.g. in libc++, that’s

max(16 * sizeof(obj), 4096); in libstdc++, that’s8 * sizeof(obj).

-

What deque needs to record/know is:

- The map and its size.

- The block size.

- The global offset of the first element off.

- Element numbers.

-

When resizing, we just need to copy all pointers, which is very cheap!

Invalidation notes#

-

For iterator:

- All iterators are seen as invalid after insertion.

- Erasing from the front and back will only invalidate the erased elements.

- This includes

.resize()when the size is reducing.

- This includes

-

For reference/pointer:

.push_front(),.push_back(),.emplace_front(),.emplace_back(),.pop_front(),.pop_back()and.resize()do not invalidate any references to elements of the deque (except erased elements).

list#

std::list<T>- Double linked list.

O(1)insertion and removal.O(1)splice.- No random access.

- Only the iterator of the erased node will be invalidated.

- Unique APIs:

.remove(val)/.remove_if(func): remove all elements that is val or can makefuncreturn true..unique()/.unique(func): remove equal (judged by==/func) adjacent elements..reverse(): reverse the whole list..sort()/.sort(cmp): stable sort.merge(list2)/.merge(list2, cmp): same procedure of merge in merge sort, so usually used in sorted list. Two sorted list will be merged into a single sorted list..splice(pos, list2, ...):(pos, list2): insert the total list2 to pos.(pos, list2, it2): insertit2to pos (and remove it fromlist2).(pos, list2, first, last): insert[first, last)topos(and remove them fromlist2).

forward_list#

std::forward_list<T>- Single linked list

- The purpose of forward list is reducing space, so it doesn’t record an additional size and doesn’t provide

.size()- If you really need it, you can use

std::(ranges::)distance(l.begin(), l.end()), but remember it’s .

- If you really need it, you can use

- There is no

.back()/.pop_back()/.push_back()/.append_range()in forward list. .insert_after()/.erase_after()/.emplace_after()/.insert_range_after()/.splice_after(): the position parameter accepts the iterator before the insertion position, so you can insert after it.- Particularly, iterators from another list in

.splice_after()is also(first, last)instead of[first, last)! - But

.insert_after()is still[first, last), since it doesn’t need to go back and may come from any container. - It’s impossible for you to provide the position instead of the one before, since it cannot go backward.

- Particularly, iterators from another list in

- So, there is a

.before_begin()/.cbefore_begin()iterator in forward list, so that you can insert at the head.

Sequential views#

- View means that it doesn’t actually hold the data; it observes the data.

span#

Introduction#

std::span<T>: a view for contiguous memory (e.g. vector, array, string, C-style array, initializer list, etc.).- Alternative to

void func(int* ptr, int size), i.e.void func(std::span<int> s). - It is cheaper way to operate on e.g. a sub-vector, and its main use case is as a function parameter.

- Span is just a pointer with a size! All copy-like operations are cheap.

Ctor#

std::vector<int> w {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6};

std::array<int, 4> a {0, 1, 2, 3};

// auto-deduce type/length:

std::span sw1 { w }; // span<int>

std::span sa1 { a }; // span<int, 4>

// explicit read-only view:

std::span sw2 { std::as_const(w) };

// with explicit type parameter:

std::span<int> sw3 { w };

std::span<int> sa2 { a };

std::span<const int> sw4 { w };

// with explicit type parameter & length:

std::span<int, 4> sa3 { a };

std::span s1 { w.begin() + 2, 4 };

std::span s2 { w.begin() + 2, w.end() }; - If you hope the span has read-only access, you need to use

std::span<const T>.- This actually makes the pointer

const T*, so it’s read-only. - However, for containers, you need to specify as

const std::vector<T>.

- This actually makes the pointer

Span with specified extent#

- Span is in fact

std::span<T, extent>, but theextentisstd::dynamic_extentby default.- cppreference: A typical implementation holds a pointer to

T, if the extent is dynamic, the implementation also holds a size. - Only C-style array and

std::arraycan implicitly construct it. - You can get the extent by the static member

extent.

- cppreference: A typical implementation holds a pointer to

Usage#

-

Random access iterators.

-

operator[]/.at()/.front()/.back()/.data()/.size()/.empty() -

.size_bytes(): get size in byte. -

std::data()/std::empty()/std::size()/std::ssize() -

std::begin()/std::end()/… -

C++20:

std::ranges::data()/std::ranges::begin()/… -

Always remember that it’s as unsafe as a pointer.

-

Notice that spans will never (except

.at()) check whether the accessed position is valid!

Making spans from spans#

-

.first(n)/.last(n): make a new subspan with the firstn/the lastnelements. -

.subspan(offset, count = std::dynamic_extent): make a new subspan begin atoffsetwithcount(by default until the last one). -

For fixed extent, you need

.first<N>()/.last<N>(),.subspan<offs, N>()to create subspan with fixed extent (.subspan<offs>()will create fixed/dynamic one for fixed/dynamic span). -

You can also use

std::as_bytesandstd::as_writable_bytesthat convert a span to a span of bytes.

mdspan#

- There are three components for mdspan.

- Extent:

std::extent<IndexType, sizes...>/std::dextent<IndexType, dimensionNum> - Layout: regulate how you view the memory.

- Accessor

- Extent:

- Primary use case:

std::mdspan<T, std::dextent<IndexType, DimNum>>.

Container adaptors#

- Container adaptors are a wrapper of existing containers; it transforms their interfaces to a new interface of another data structure.

- They usually don’t provide iterators.

stack#

- Stack is a LIFO data structure.

- The default provided container is deque.

- APIs:

.pop().push(val)/.emplace(params).push_range(Range).top():the element at back.

queue#

- Queue is a FIFO data structure.

- If you want to use list, forward_list is obviously better; but it doesn’t provide

.size()and.push_back(), so you may write a small wrapper yourself.- Notice that you can choose to not provide

.size()if you don’t use it in queue; this is benefited from selective instantiation.

- Notice that you can choose to not provide

- APIs are same as stack except

.top(). Use.front()and.back().

priority_queue#

- It’s in fact max heap. (min heap needs the parameter

std::greater<T>) - it can always provide the current maximum element in after inserting a new element or popping the last max one.

- Constructing the heap needs only , which is cheaper than sort.

flat_set/flat_map/flat_multiset/flat_multimap#

std::flat_map<Key, Value, Compare = std::less<Key>, ContainerForKey = std::vector<Key>, ContainerForValue = std::vector<Value>>- It’s in fact an ordered “vector”!

- It doesn’t have any redundant data, and is more cache-friendly obviously.

- Complexity:

- For lookup,

- For insertion/removal,

- For iterator++,

- The iterator is also random-access iterator!

Tuple and structured binding#

tuple#

-

e.g.

std::tuple<int, float, double> t{1, 2.0f, 3.0};:std::make_tuplestd::get<0>(tuple)orstd::get<int>(tuple)operator=,swap,operator<=>std::tuple_size<YourTupleType>::value,std::tuple_element<index, YourTupleType>::typestd::tuple_cat: concatenate two tuples.

-

std::tie: creates a tuple of lvalue references to its arguments or instances ofstd::ignore. -

Use case: for

operator<=>that cannot be default while you still want some form of lexicographical comparison, you can utilizeoperator<=>of tuple!

class Person {

public:

enum class Gender { Male, Female } gender;

std::string name;

int age;

std::weak_ordering operator<=>(const Person& another) const {

return std::tie(age, name) <=> std::tie(another.age, another.name);

}

}std::paira specific case of astd::tuplewith two elements.- Additional APIs:

first_type/second_type/first/second

- Additional APIs:

std::pairandstd::arrayis also somewhat tuple-like thing and can use some tuple methods, e.g.std::get.

Structured binding#

auto& [...] {xxx}xxx: a tuple-like thing.- Structured binding is declaration, so you cannot bind on existing variables.

- Instead, for tuple and pair, you can use

std::tie(name, score) = pairto assign.

- Instead, for tuple and pair, you can use

- You can use

_as variable name to denote “it is dropped and never used except for constructing it”.- e.g.

auto& [_, score] : score_table

- e.g.

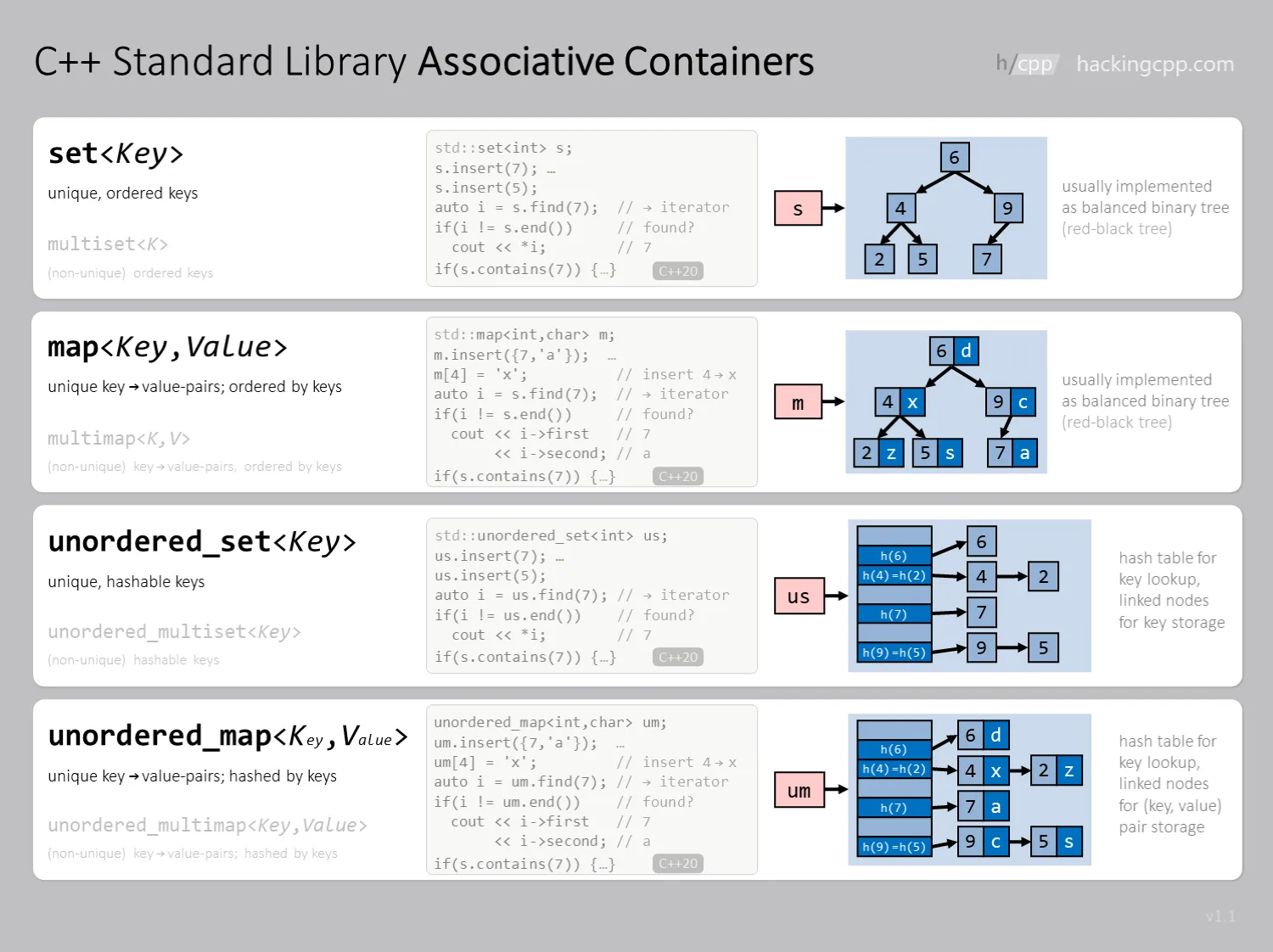

Associative containers#

- They associate key with value. The value can be omitted.

- The Key is unique; a single key cannot be mapped to multiple values.

- Ordered one needs a compare function for “less than”.

- It’s BBST (balanced binary search tree), and search, insertion, removal are all .

- Unordered one needs a hash function and a compare function for “equal”.

- It’s (open) hash table, and search, insertion, removal are all expected while the worst is , if all keys are hashed as the same key.

- They’re all node-based containers.

Ordered containers#

map#

-

std::map<Key, Value, CMPForKey = std::less<Key>>CMPForKeyshould be able to acceptconst Key.

-

operator[]/.at(): accessing by index.operator[]will insert a default-constructed value if the key doesn’t exist. You cannot use it inconst std::map..at()will check whether the index exists; if not,std::out_of_rangewill be thrown.

-

Bidirectional iterators.

- Notice that the worst complexity of

++/--is 𝑂(log 𝑁) since you may go from the rightmost child of the left subtree to the right subtree. - However, iterating from begin to end is , so

++/--is still on average.

- Notice that the worst complexity of

-

Key-value pair is stored in RB tree, so iterator also points to the

std::pair. -

You can use structured binding to facilitate iteration.

-

Notice that key of map is

constto maintain order; you need to erase the original and insert a new one if you want to change key.

std::map<std::string, int> score_table {

{ "Li", 99 },

{ "God Liu", 100 },

{ "Saint Liu", 99 },

{ "Liang", 60 },

};

for (auto& [name, score] : score_table) {

std::println("name: {}, score: {}", name, score);

}-

.size()/.empty()/.clear() -

.find(key): get the iterator of key-value pair; if key doesn’t exist, returnend(). -

.contains(key): alternative toif(auto it = map.find(key); it != map.end()) {} -

.count(key): get the number of key-value pair referred bykey. -

.lower_bound(key)/.upper_bound(key)/.equal_range(key) -

operator=/operator<=>/swap/std::erase_if -

Insertion: may fail if the key exists. Retuens

std::pair<iterator, bool>..insert({key, value}).insert_or_assign(key, value): overwrite..emplace(params): the params are used to construct pair..try_emplace(key, params): the params are used to construct value.- You can also provide a hint iterator for insertion.

-

.erase(key)/.erase(iterator pos)/.erase(iterator first, iterator last) -

.extract(key)/.extract(iterator pos)- Return

std::map<Key, Value, ...>::node_type. - Use

ret.empty()oroperator boolto determine whether the key exists.

- Return

-

.insert(node_type&&)- You need to pass

std::move(node)or directlyxx.extract(yy)to this param. - Return

insert_return_type, a struct with{ iter position, bool inserted, node_type }.

- You need to pass

-

.merge(another_map/multimap):- Existing keys will not be moved.

-

.insert_range(...)

set#

- It is just a map without value.

- The only difference with map is that it doesn’t have

operator[]and.at(); the iterator points to only key instead of key-value pair.

multimap/multiset#

- Multimap cancels the uniqueness of key. So, you cannot use

operator[]and.at()too. - These equivalent values are in the same order of inserting sequence.

- Nodes of multimap and map can be exchanged.

- The

operator<=>check equality one by one, so even when two multimap stores same things with only different orders in equal keys,==is false.- Particularly, for

==/!=instd::unordered_multimap, it’s only required that they have same values on each key.

- Particularly, for

Unordered containers#

unordered_map#

std::unordered_map<Key, Value, Hash = std::hash<Key>, Equal = std::equal_to<Key>>- Many types have

std::hash, e.g.std::string,float, etc., so you can use them as key directly. - Customize hash:

struct Person {

int id;

std::string name;

};

template<>

struct std::hash<Person> {

std::size_t operator()(const Person& p) const {

return std::hash<int>{}(p.id) ^ std::hash<std::string>{}(p.name);

}

};-

Load factor: : as more and more elements are inserted, there will be too many elements in each bucket, which increases the complexity of finding by key.

-

Rehash: when load factor is high, we need to enlarge the size of bucket array to make elements scattered again.

-

C++ regulates that rehash will invalidate all iterators.

-

.bucket_count() -

.load_factor():size() / bucket_count() -

.max_load_factor(): when load factor exceeds this limit, rehash will happen.You can set it by .max_load_factor(n). -

.rehash(n): makebucket_count()=max(n,ceil(size()/max_load_factor()))and rehash.rehash(0)may be used to adjustmax_load_factor()to immediately rehash to meet minimum requirement.

-

.reserve(n): reserve the bucket to accommodate at leastnelements. -

Get a bucket directly:

.bucket(key): get the bucket index of the key..begin/cbegin/end/cend(index): get the iterator of the bucket at index..bucket_size(index): get the size of bucket at index.

unordered_set/unordered_multimap/unordered_multiset#

- The relation of unordered ones are same as ordered ones.